Work by Sarah Sze, photographed by Kevin Walker

This is documentation of a seminar about documentation and exposition in relation to practice research, run by Kevin Walker in July 2023 and July 2024.

This seminar is about process, tools and materials as well as products of practice research. ‘Exposition’ refers broadly to a wide range of outputs, as used in the Research Catalogue. We differentiated it from externalisation, as used for example in activity theory in terms of how and what knowledge is internalised and externalised; and elicitation, such as the use of speak-aloud protocols and stimulated recall techniques to externalise such knowledge.

Since participants in this seminar have so far been generally situated within the arts, that is where the focus has been, but with reference to scientific and technical methods for documentation and exposition.

I started by showing recent work undertaken as part of the SPACEX project. I only used materials which were left where they were found, so the photo documentation travelled much further than the finished objects, which were likely to be collected by a single person or else discarded.

What does it mean to practice? What makes practice research? We differentiated from research-based practice, which could broadly indicate any type of research done for practice. There are many variations of the term, but we did not go into academic discussions, referring generally to practice as a research method. In this case, it is the rigour that makes it research.

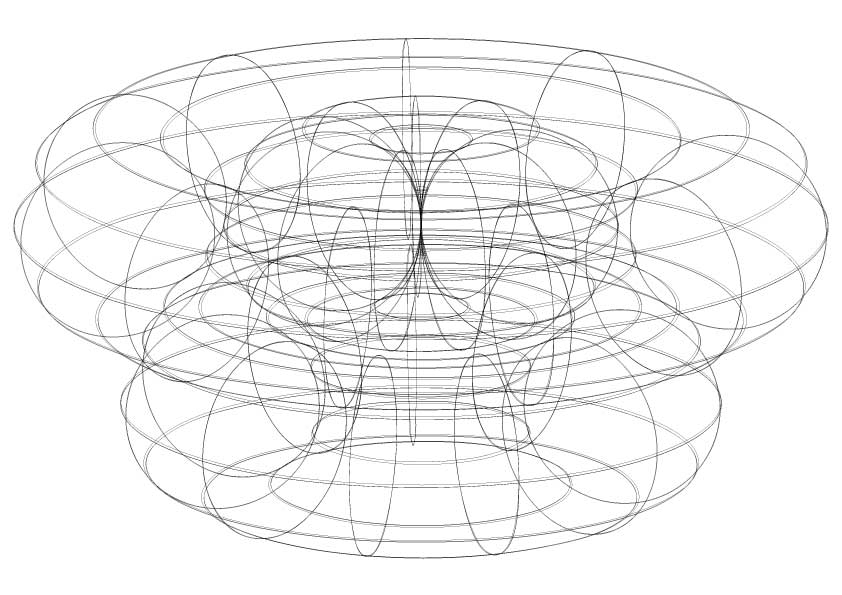

Finding a simple binary distinction limiting, I extruded the Venn diagram to create a torus, in which research and practice become a single surface across which a practice-researcher can move.

However, we should perhaps add a third element: theory. If research refers broadly to a wide range of approaches, designs and methods, theory is distinct from practice, and may or may not be included in research.

Extruded into three dimensions however, a triple Venn diagram becomes too complex to read easily (though some practitioners depict their process as even messier).

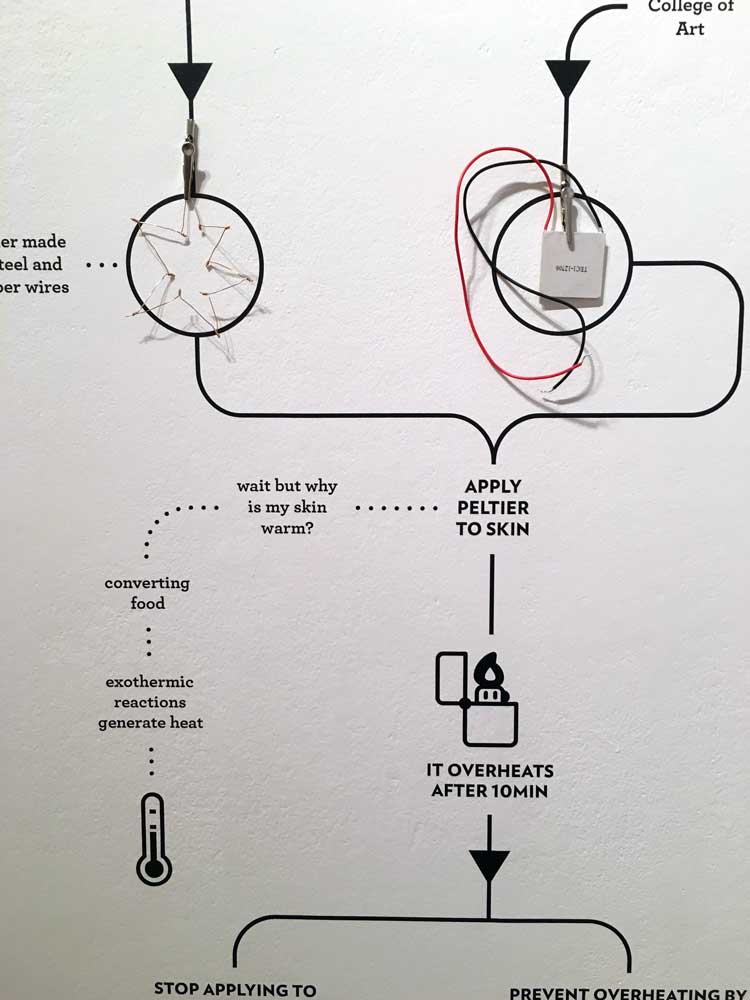

Great documentation of process from student Meret Vollenweider, who investigated the research question, ‘Can I generate enough electricity from my body for my daily needs?’ Find out more about the project here.

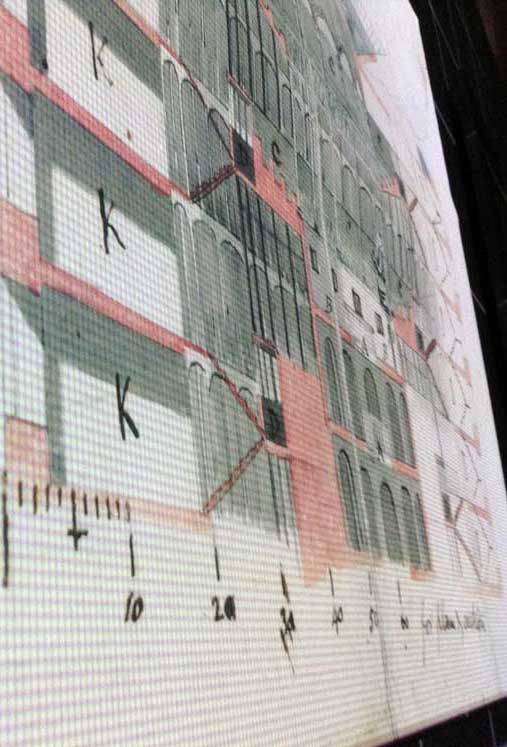

It is often useful to make your own instruments. For this Micro Research workshop, lecturer Caroline Claisse made a one-metre square frame for students to explore different perspectives in the environment. This took inspiration from artists such as the Boyle Family. (photos courtesy of Caroline Claisse, used with permission)

Practice research requires the researcher to be both insider and outsider (as in ethnography), which can be difficult to balance. According to O’Donoghue, this means resisting the imperative to record immediately or force an interpretation from a distance; instead it means immersing oneself directly in the research experience. (Participants pictured here: Thomas Gardner, Nicolas Marechal, Colin Priest)

In artistic research it can be more useful to think in terms of validity, not reliability or generalisability, as in science: Can we learn from it? is there a good reason for doing it?

Practice research departs from practice, by making and communicating new understandings – not only making work. Where is knowledge in your work? This might include nonlinguistic and tacit knowledge which may resist capture, coding, or classification. If you start off defining research as only what is measurable, you will miss a lot. ‘Data’ is a science word; documentation is more suitable to artistic research.

Documentation and exposition may be about the creation of a narrative. Artist-researchers can control the narrative in the interpretive materials they provide alongside their work, instead of ceding control to the viewer or critic.

Sometimes the documentation becomes the work, as in this example by Artist Placement Group, which placed artists in companies and government between 1966 and 1976.

Documentation can simply serve as evidence that something happened, or can communicate the deeper aims of the work, according to Coventry postgraduate researcher Alex Parry.

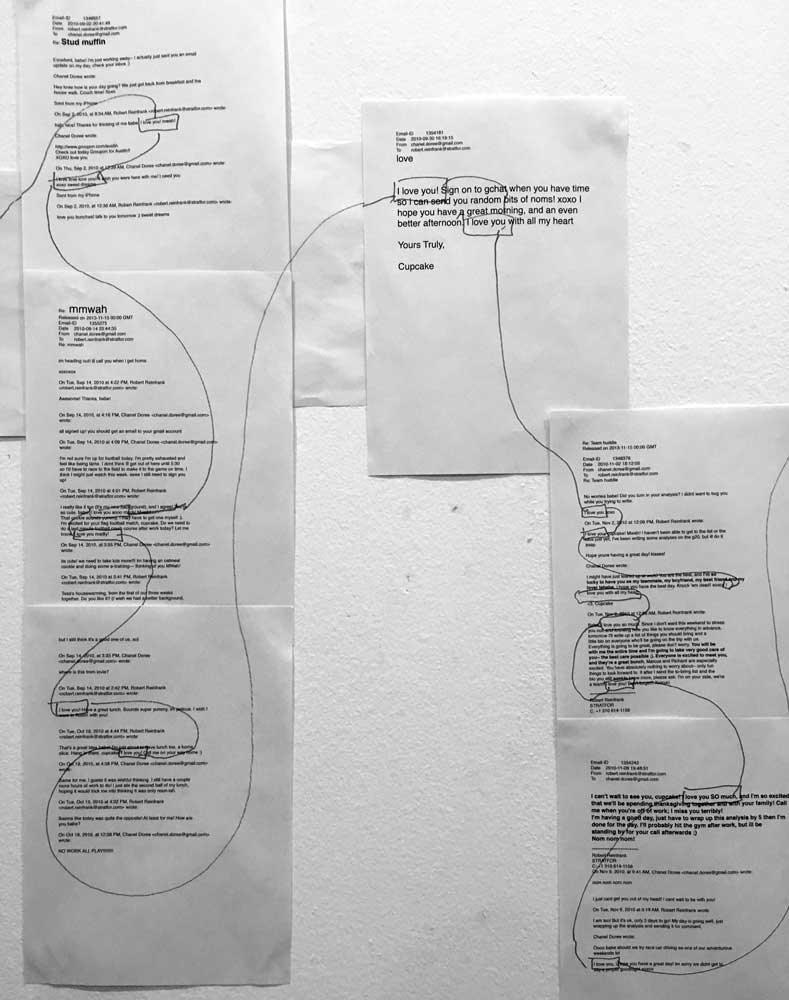

Here is another example: artist Anna Ridler printed 10,000 documents from the Wikileaks archive, and traced a love story in emails between two US government employees. This became an artwork, with the addition of an augmented reality app on an iPad – see Anna’s website for her always-excellent documentation.

Artist Sarah Sze shows the value of printing and saving everything – this is from an exhibition of hers, in which she exposes the process, which in turn becomes part of the work.

Another artist, Alexandra Mir, also told me to save everything – because years later, her entire archive was acquired by an institution.

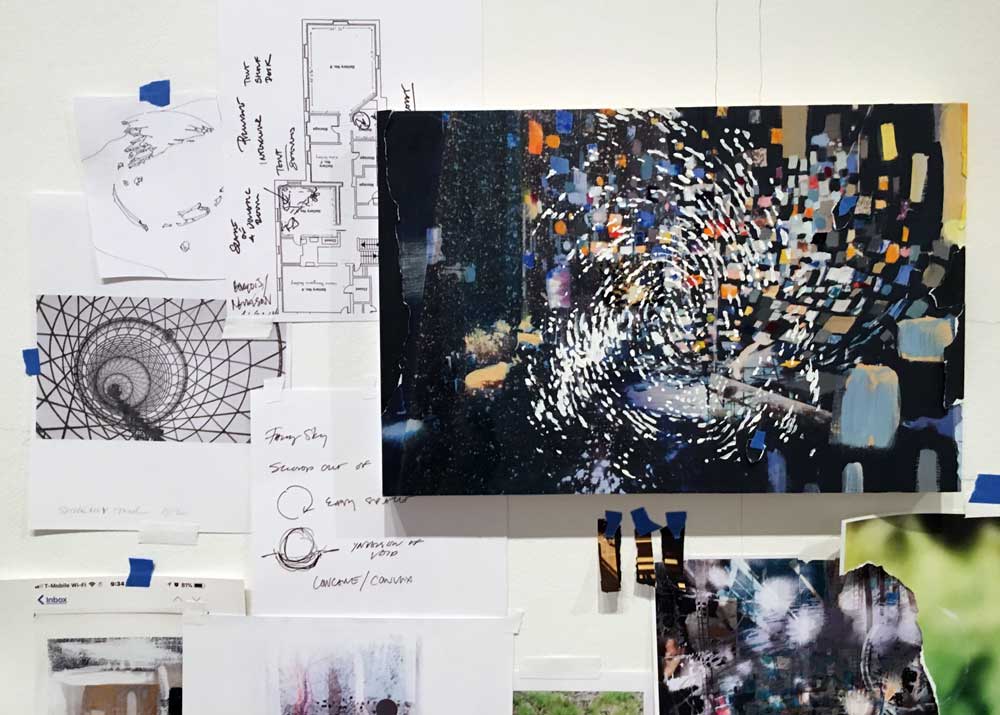

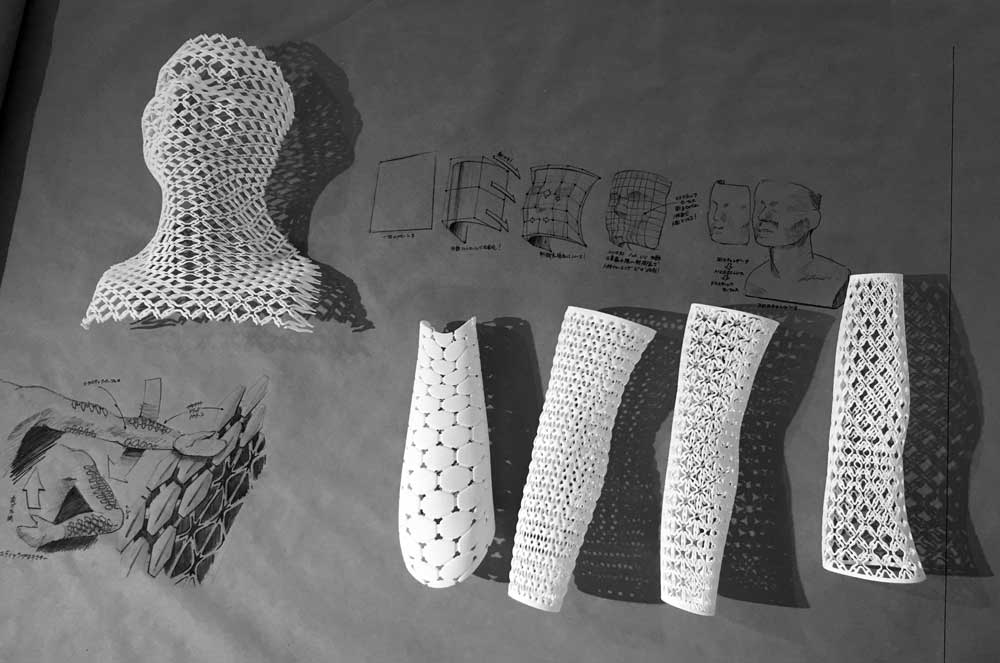

Foregrounding the process of production can provide one compelling narrative, as in this 2016 robotics exhibition at University of Tokyo.

Simple before and after images immediately tell a story without words.

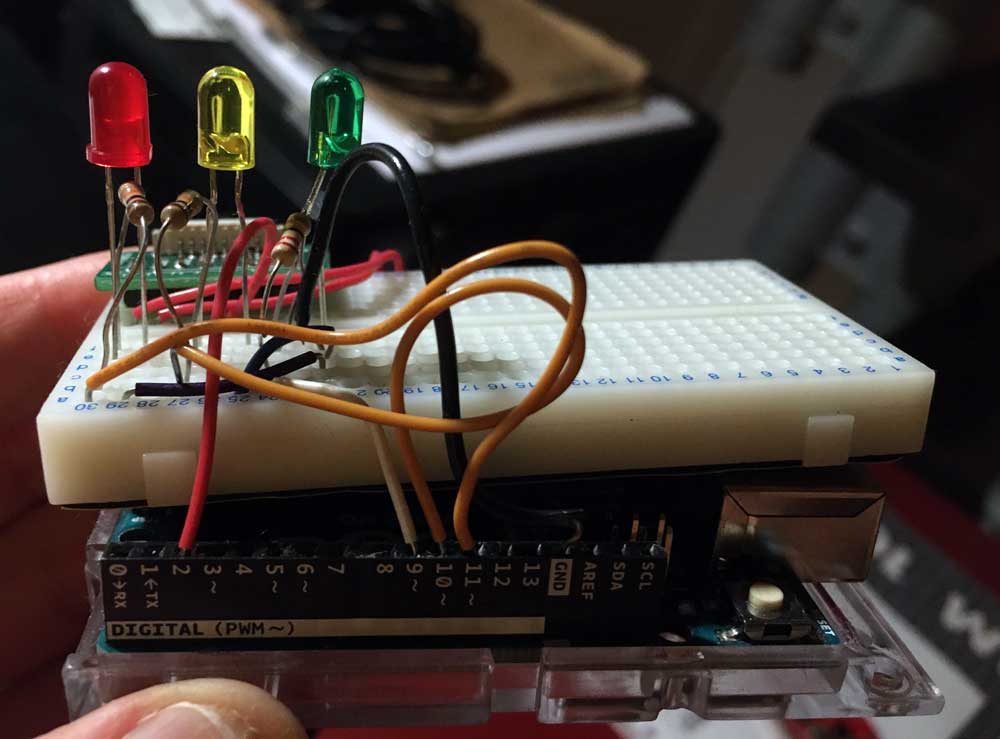

I photograph the process not only for documentation, but as a memory aide: Which wire goes where? A blog or website is a common way of exposing the process. Another narrative can be told in comments placed within programming code: a narrative for a very specific audience.

Finally: If you can get a professional to document your work, you get not only great images but another perspective. This photo by Carl Bigmore of an exhibition I curated. Work in the foreground is by Celeste Camilleri and Jordan Edge.

(All other photos in this post are by me.)